Identifying Inclusive Design: A Foundation

Updated August 15, 2024Key topics covered:

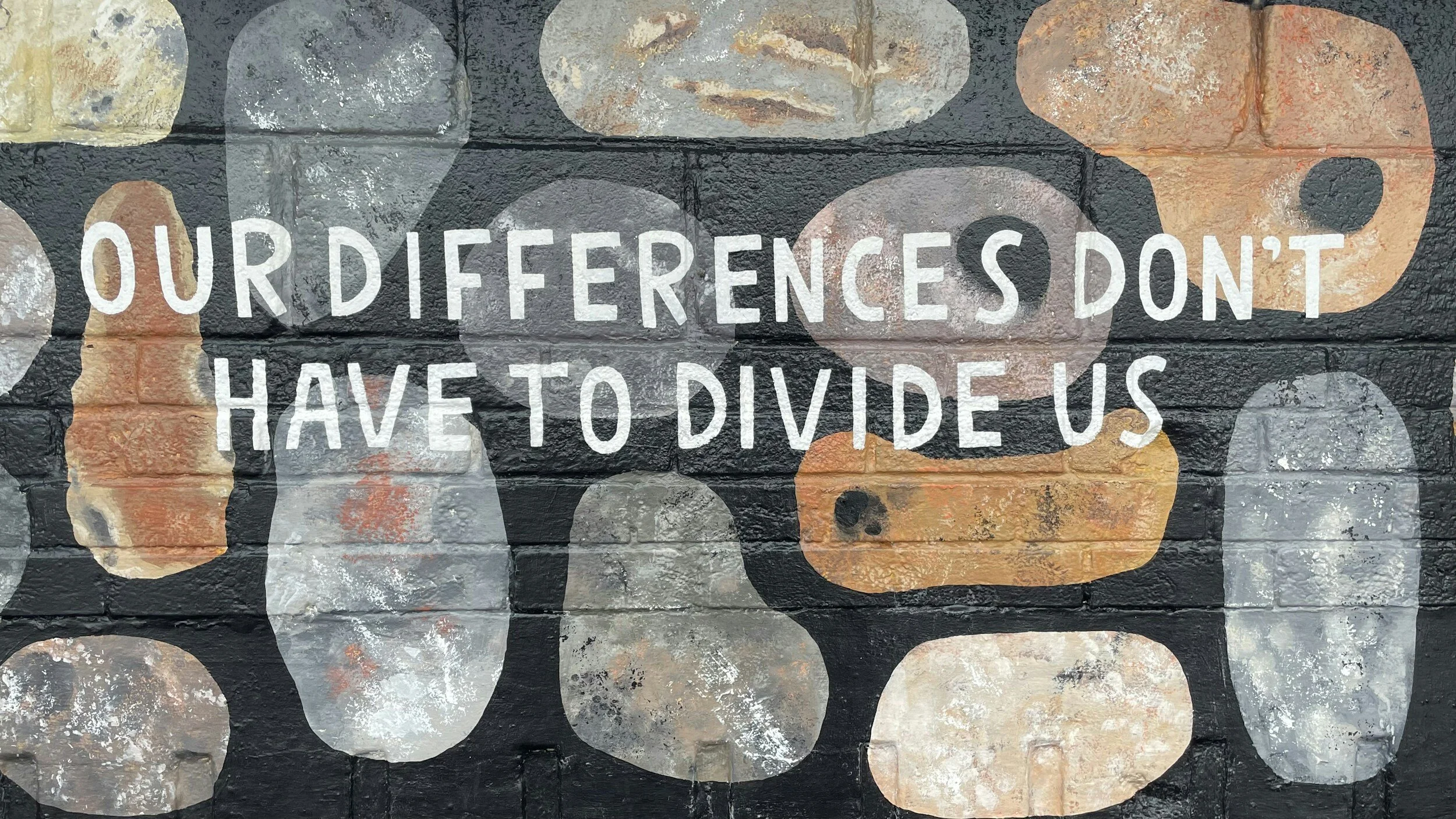

The term inclusivity is a broad term that includes all types of users, individuals, and business needs by designing with empathy.

There are many false beliefs about inclusivity and inclusive design that are often rooted in fear and bias, yet this defensive is often in response to a formal fallicy.

Inclusive design means that the practitioner approaches the problems with empathy, and that creates a safe space for their client to share their lived experiences.

Inclusive design resources for interior design

Forward

Inclusivity is for everyone. It is not exclusive or one idea or another and it considers everything for everyone by designing with empathy.

While I continue to speak about inclusivity since inaugurating Identifying Inclusive Design as an educational CEU for the design industry at events and webinars across North America. I encourage our readers to apply critical thinking to uncover our biases as a society with regards to the built environment. This article is to clarify any confusion people might associate with the term inclusive and the fundamentals needed to the practice of interior design and architecture.

Upcoming dates to hear Corey speak : Identifying Inclusive Design are on September 27 at IDS Vancouver 2024

CEU: 1.0 CEU IDCEC NKBA

In the world of human-centred design, inclusive design is the intersection of accessibility, usability, diversity, and space planning. With an open dialogue, you will learn about the three-dimensions of inclusive design and how to apply them with the client, contractor, and creative paradigm. Reviewing three inclusive design case studies, you will learn about techniques and tools to utilize in and out of our built environment. Be bold, be colourful, and be you for this session.

If you would like to book Corey to present this topic at an industry event or webinar, please reach out. We would love the opportunity to share.

The Beginning

Over the past decade, our political climate has been threatening marginalized individuals and eroding at needs and creating greater differences. While the role of a centralized government is to provide us with a common law society, infrastructure, universal healthcare, safe housing, food stability and economic stability (among others), politicizing marginalized citizens and removals of rights and protections are ongoing with lawmakers whom seem to believe that they are excluded from the inclusion movement. The common belief is that we spend up to 90% of our time indoors(1) and I would argue that the rights of all for safe, healthy, and quality access to the built environment is of paramount concern.

In 2021, while I was working on the NKBA’s Kitchen & Bath Planning Guidelines with Support Spaces and Accessibility, 4th ed. as a content coordinator with other subject matter experts, it struck me that the much of the issues we were addressing within the guidelines were about including as many individuals and users in kitchens, baths, and associated spaces as possible. As recently as last week, I commented on an Instagram post by the Global Cycling Network on the lack of inclusivity in the cycling community and the amount of vitriol, discrimination and misogyny in others responses were exceptional, but also highly problematic because they were riddled with misunderstanding about what inclusivity actually is.

The false beliefs about inclusive design

The term inclusive design within interior design is often misunderstood. Outside of our professional practice, the term “inclusivity” is often misidentified and politicized (even weaponized) as a movement expressing rights and freedoms for individuals to express gender identity and sexual orientation (SOGI). While SOGI is an important part of inclusive design, it is not exclusive to inclusivity. The unnecessary bias and fear-mongering is highly politicized because it lacks the key human emotions that are integral to inclusivity. Derogatory terms such as “the alphabet group” are tossed around altruistically and narcissistically, but this is a texas sharpshooter fallacy and extreme conservative beliefs that are unfounded and rooted in fear of the unknown.

We are all uneasy with new things and, therefore, it is important to define what inclusive design actually is. Firstly, everyone (across all channels) must stop jumping to conclusions about what they do not know or understand and start with becoming curious about what inclusive design really is - because it is actually for everyone.

Values of inclusive design

Fundamentally, inclusive design is an approach that considers everyone’s needs in their past, present, and future forms and abilities, regardless of ones political, cultural, or religious beliefs because everyone is automatically included. Inclusive design provides the same interior environment access rights to individuals who are 4 months pregnant verses a transgender individual, and also includes wheelchair users, families with differently abled children, and users who use corrective lenses and have varied eyesight. These examples are only the beginning and, simply put, at the forefront of inclusive design are the marginalized because these are the individuals that we must take care of.

Inclusive design is like an auditorium where the methods of universal design, accessible design, and (the unfortunate term) barrier-free design are commingled with the marginalized and different stakeholders and provide a holistic and inclusionary method to solving a design problem. When a professional interior designer refers to each of these terms, they are talking about using an evidence-based approach in the seeking of a physical design solution to a problem. Meaning, in order for the interior designer to generate a concept, they must first consider the evidence and determine the problem by following the scientific method.

The pivotal point of inclusive design is to design with empathy.

Design it, but with empathy

Empathy is not an emotion, but it is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. Empathy is sympathy without the emotion. Designing with empathy requires the interior design practitioner to step outside of their beliefs and values, check their biases, and tackel the key problems that the marginalized stakeholder is identifying.

Empathy is uncomfortable.

Empathy is also euphoric and two things can be true at the same time - it is completely possible.

As a professional interior designer, here are 2 examples of the use of how I have used empathy in my projects to create an inclusive design solution.

Example #1

A client has approached me to design a dungeon-type of space with a St. Andrews Cross, a display area for their sexual toys, and enough space to for them to practice what they play. While I may have known nothing about these things before our conversation, I approached the space planning needs with an understanding of the activities, performance, and curiosity. I did not deep-dive into this form of sexual expression because it was not of interest to me, but, rather, I wanted to help my client have a safe space that considered their needs for privacy, acoustics, and pleasure in a safe space for them.

Example #2

A client who is a senior paraplegic and a diabetic approached me to design a renovation for their downtown condominium so that they can express their design style and be more independent. While I am not a wheelchair user, diabetic, or a senior, the client has lived in their body with their experiences the longest and they are the expert. The guidelines helped formulate an overall design plan, but through the design and consultation process I used empathy to understand the challenges they phased in the built environment by demonstrating the problems. From there, I developed a personalized design solution.

Example #3

A corporate workspace client runs a busy ophthalmology office with 3 doctors and 7 medical office assistants (MOA). Information gathered during the programming phase uncovered challenges that the MOA’s face with patients of various languages and visual acuity, which can leads to patient confusion and stress because the sequence of testing for each patient is different with different ocular machines. To address this problem, I listened to every MOA in a personal interview, asking questions about what and why, learning about their process problems so I could best address their unique needs - because this example was everything but textbook. Planning a “Testing Bay” where the patient can move through the sequence of machines without getting out of their chair and navigating to another area was paramount in solving the repetitive tasks and eliminating patient confusion. The result was increased efficiency with better task management for the worker, thereby increasing clinic revenues.

Each of the above examples are how empathy can be applied at various stages with a variety of solutions. While they are unique to each other, and a more expansive step-by-step would be beneficial in a future article, they illustrate the importance of applying empathy at a variety of design planning stages.

Design From the Margins (DFM): The Approach

The approach of design from the margins (DFM) identifies that when we empathize with the marginalized, or the individuals who are often pushed aside by the majority (such as those with varied physical needs, cognitive impairments, visual and audible impairments, olfactory impairment, or any other disability needs) in order to return to the primary focus of the design solution, interior design professionals much include the marginalized individuals from the jump. It is equally important to identify any personal biases that the interior designer may have by checking in with their illogical fallacies, critical thinking, and by also focusing less on their personal revenue objectives for a quick, but thoughtless and flawed, design solution. The best approach here is to slow down, think it through, visualize the individual needs, and sketch prototypes that could iterate and resolve a tricky problem.

Gensler approaches inclusivity with this statement:

“As part of a business strategy, diversity and inclusion are often driven by the interests of customers and clients, but also by the well-being of professionals and their opportunities to achieve success. That means organizations must foster an environment where people feel comfortable having a dialogue not just about their similarities, but about the differences and uniqueness they bring to the table.”

While I continue to speak about this topic, most recently at IDS Vancouver and planned in a couple weeks KBIS 2024 in Las Vegas, NV, it would be best service that the reader stop and assess what is really being talked about here. Applying critical thinking will lead you to uncovering your biases, the potential of harms that you create, and deep fallacies about this important fundamental to the practice of interior design and architecture.

Inclusivity is for everyone. It is not exclusive or one idea or another and it considers everything for everyone by designing with empathy.

Inclusive design resources for interior design

Kitchen & Bath Planning Guidelines with Support Space and Accessibility, 4th ed., NKBA, 2021

Achieving Inclusivity in the Design Process, Gensler, 2019

Emma More, Making Workspaces Inclusive Through Design, Archdaily, 2023

Blaine Brownell FAIA, A Case for Inclusive Design, Architect Magazine, 2018

Afsaneh Rigot, Design From the Margins: Centering the most marginalized and impacted in design processes - from ideation to production, Harvard Kennedy School - The Belfer Center, 2022